Age in Aging Places

/These two case studies are about the home city where we grew up. Hong Kong has transformed itself from a small fishing village to a global metropolitan city in the past 150 years. Of all many economic, political and social policies that facilitate the changes, housing policy is one of the key components. The foresight of the housing policy has enabled Hong Kong to overcome many demographic and economic challenges. The two case studies selected are under the development of the Hong Kong Housing Society (HKHS), a non-profit organization established in 1948 in response to the devastating aftermath of Japanese occupation in 1945 and the continuous influx of refugees and immigrants into Hong Kong.

The Ming Wah Estate (MWE, 明華大廈, 1962) in Sau Kai Wan District and Lai Tak Tsuen (LTT, 勵德邨, 1975) in Causeway Bay District on the Hong Kong Island represent different important HKHS developmental phases in the 1960's and 1970's, respectively. The tenants who had the privilege of moving into these two estates tended to be young generation families, some of which were three generation families. Leung was one of the many Hong Kong children who lived and grew up in this type of low rent housing. He moved to MWE when he was 6, and relocated to LTT at age of 14.

Shortage of land, particularly flatland, in Hong Kong has been a challenge for housing and economic development. The common practice of the government and private developers is to demolish older and shorter buildings and replace them with new and tall ones and/or new constructions carried out on land claim from the sea with stones and mud removed from hills and mountains where spaces are created for new constructions. Similar to many other buildings in Hong Kong, MWE and LTT are built on hills and mountains. Busy construction and deconstruction are integral parts of everyday life in Hong Kong.

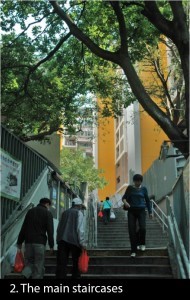

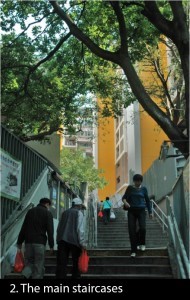

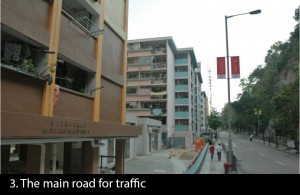

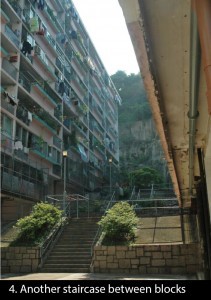

MWE can be considered an older residential estate by Hong Kong standards. It consists of a group of 13 buildings (see Picture 1) with various heights ranging from 6 to 20 stories. In order to house more tenants, Black 25 had been reconstructed, while the rest remain the same while undergoing major modification and maintenance. Picture 2 and Picture 3 show the major access routes to facilities such as public transportation, and markets via the main staircases and road, respectively. The residential blocks are built between the staircases and this road. Between the residential blocks is another steep staircase which connects the main staircase and the road (Picture 4). These pictures were taken in 2009 when major maintenance had been largely completed.

In former times, there was no public transportation directly serving the residential blocks. Residents had to disembark from any public transportation outside the estate and either climb the main staircase or walk on the road to reach their homes. When they arrived at their block, depending on the floor of their residence, they had to climb the stairs to arrive home (Picture 5). There were no elevators in the buildings, except in Block 13.

When the families were newly established, and the residents were younger, the climbing was not an issue. The children of these young families grew up in the rapid metropolitanization of the 1980’s. Some of them studied abroad. Some embraced western values and formed their nuclear family after marriage. Some emigrated to other countries due to various reasons, particularly during late 1980’s and 1990’s. Their aging parents are left behind in their empty nests. In order words, the public housing like this is experiencing aging, not the buildings, but also the residential population. How could these aging residents climb so many stairs as part of their daily activities?

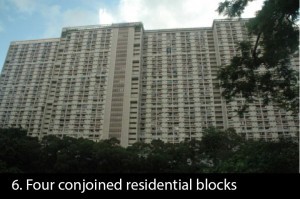

LLT’s story is not much different, although the estate was built later and the facilities are more up-to-date. However, elevators only stopped at every three floors. There could be some good reasons why it was designed in such a way, including cost effectiveness and control of the flow of people. Look at the 4 conjoined mega residential blocks (Picture 6). Several thousand residents used the 6 elevators located in the middle of the structure during rush hours. These 6 elevators arrived at floor levels in pairs, (for example, two elevators serving between 11th to 18th floors only) and only stopped at every three floors within the levels. This setup aided the flow of people. But the residents had to use stairs to reach their floors if the elevators did not stop at their level. One of the rest areas was constructed next to the hill, and the only access to it was by climbing. Accessibility required by stair climbing has become a challenge for many current aging residents.

Instead of paying high costs of maintenance of the two aging estates, HKHS could have demolished them and replaced them with higher residential buildings. At the same time the award-winning design of the newer LTT buildings seemed to merit their maintenance. One of the reasons behind the decision to keep the two estates is based on the concept of “aging in place”. According to numerous gerontological studies, relocation of the elderly does not benefit their well-being. Thus, the elderly have a right to age in a familiar place as long as they wish. One way to improve the ‘physical comfort’ of the elderly residents is to add elevators or modify the existing elevator system. Now all the blocks in MWE has a newly built elevator (Picture 7 and the orange painted structure attached to the building in Picture 8).

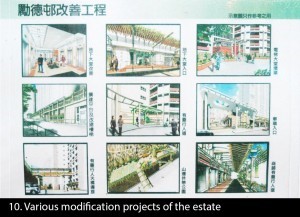

LTT is experiencing additional modifications. Although each pair of elevators continues to serve only between certain floors, now they stop at every level. Picture 9 shows the plan of opening up the wall for the elevator stop. In order to encourage the elder to exercise more, a bridge is connected to the rest area and the building so that they do not need to climb stairs. Picture 10 posted at the estate’s lobby shows all the modifications in the estate. Projects include adding canopies to provide protection from the sun and the rain for the residents. Also, the aging population of the residents justifies conversion of basketball courts into green areas. The bottom two figures in the picture from the left show the bridge from two perspectives. Picture 11 shows the actual bridge.

Another thoughtful renovation is to repave the surface of all the stairs in open area. Before the stairs were in ordinary plain grey concrete surface. Now the tiles are anti-slippery and are in contrasting colors (Picture 12). Research studies find that high contrast colors help the elderly see the depth.

Architecture builds to suit the human needs and fulfill human desires. Yet, the ideal forms and designs should not only be aesthetically appealing, but also facilitate human interaction and particular needs. A piece of humane architectural space relies on conception, imagination, and social research that help understand human behaviors. These two case studies also shed light on any city which experiences an aging population. Beijing and Shanghai are good examples. Many of the houses in Hutong (胡同)and Linong (里弄)are worthy of preservation as cultural heritage. Many elderly people who are still living there should have an option to ‘age in place’. Policy makers, urban planners, architects, developers, social researchers and any other related agents should develop a collective effort to develop strategies congruent with these goals before considering demolishment.